Why Found a Startup?

Author's note: This will be the first of a series of articles about founding a tech startup

Building a startup is hard. We have heard plenty of scary stories about startups that ran out of money and had to liquidate, do mass layoffs, return all their raised capital, or do all the above combined. This article from StartupTalky has many good statistics about startup failures. The most glaring one is that 9 out of 10 tech startups fail within the first few years of their foundation.

Why are the failure rates so high for tech startups? Why risk building them if other, safer career paths are available? Let's do a deep dive on the various whys:

- Why are startup failure rates so high?

- Why do people continue to build startups?

- Why do tech startups grow more rapidly?

- Why is founding tech startups not for everyone?

- Why do founding teams increase the success of startups?

- Why am I writing all this?

Why are startup failure rates so high?

Part of the reason startup failure rates are so high is that startups, by definition, are trying to establish and operate a new and unproven business model that has yet to be proven successful in the market they are targeting.

This differentiates a tech startup from, say, a chain of supermarkets. Supermarkets as a business model have been proven to be successful in various markets since:

- There exists an apparent demand for the business.

- A cost-efficient supply chain already exists and has been established.

- The value the business delivers to its customers is high enough to extract a sizable margin and ensure the company's sustainability and profitability.

In contrast, a tech startup building a new product for an unproven market has to figure out all three fundamental questions at the same time:

- Will there be any demand for the service we plan to build and provide?

- Will supplying the service in a cost-efficient manner present a challenge? (or even possible at all?)

- Will the value we deliver to our customers be high enough to extract a healthy margin that can ensure our business' sustainability and profitability?

Answering those questions is the hardest part of building an early-stage startup. So much so that some VCs encourage founders to skip all three parts, copy a successful startup from another region, and try to deploy their formula for the local market. This is not a guaranteed success because what works in one market might not work in another due to the various differences between both markets.

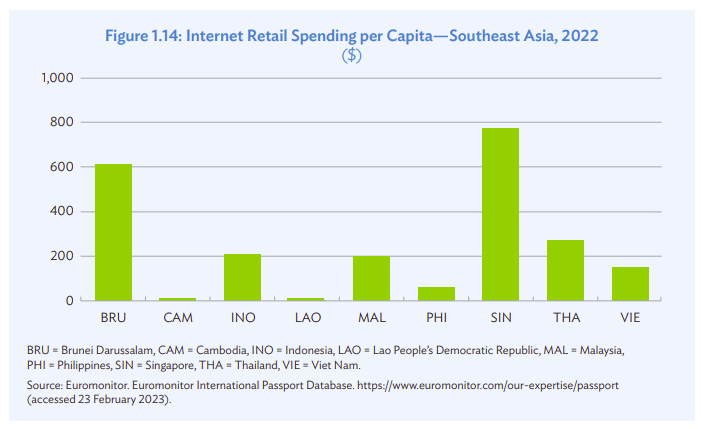

For example, as seen in the following chart, in developing markets like Indonesia, the e-commerce transaction value for each user (which affects the margin the e-commerce company can extract) is relatively low compared to countries such as Brunei or Singapore. A startup business model that works in those regions may not work as successfully when copy-pasted to Indonesia.

These difficulties in finding a working business model are one of the core reasons why startups, especially early-stage ones, often pivot their model in search of a product-market fit. This pivot can be drastic, but it is often necessary to unlock the right value for the customers or to realign the supply/demand for what the product provides.

This list provides examples of large startups that successfully pivot to find their PMF. Do you know that Whatsapp used to be a platform to display user status instead of a messaging app? YouTube's initial idea was a dating site where people could upload intro videos about themselves.

One general theme of the above pivots is observing what customers do with the product when it is launched and then investigating whether that use case brings more value to the customers than the founders' original value proposition.

For example, when Yelp launched, its initial idea was to be an email-based referral network for asking friends for recommendations. However, they observed that their customers were using the "Real Reviews" feature more because they value unsolicited human reviews, so Yelp pivoted towards being a review platform.

Listening to our customers is a good strategy to follow since a common pitfall for founders at the pre-PMF stage is focusing too much on building what new features they want (or even what their investors want), hoping that the next feature will be the one that hits the product's market fit. As we see above, listening and aligning with customers' needs are often more effective.

Even after finding a product-market fit, there are no guarantees that the fit will continue to exist as the startup grows or the market condition changes. This means later-stage startups sometimes have to execute drastic pivots as the nature of their business shifts. (Which, unfortunately, in some cases manifests as mass layoffs as the whole organization reorients itself towards a different business model)

To recap, startups have huge failure risks because they are braving new business models full of uncertainties, and even finding traction does not guarantee that the startup will have a sustainable and profitable business later on.

To make an imperfect analogy, it is as if the founders are driving a steam train while simultaneously building the tracks to reach their destination before the coal runs off. But if founding a startup is demonstrably very challenging, why do people keep building them?

Why do people continue to build startups?

Perhaps, to no one's surprise, a large part of the drive is the money. Successfully founding and scaling a well-executed startup can be one of the fastest ways for founders to grow their wealth.

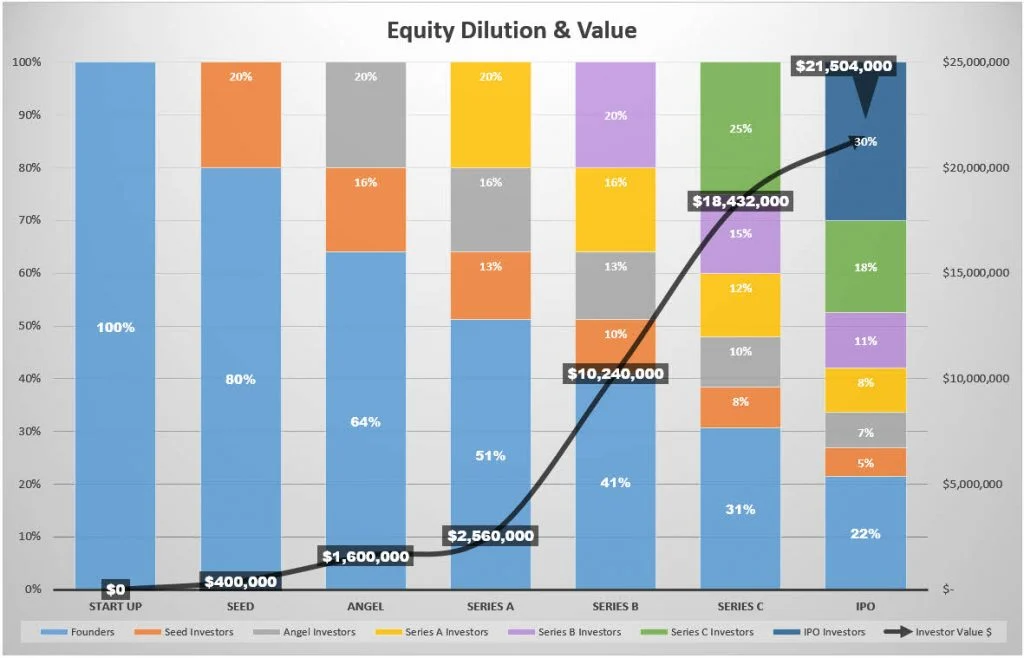

To illustrate this wealth building, I want to direct your attention to the following hypothetical chart that tracks the stages or rounds of a startup, from founding to IPO:

To understand the chart, we must realize that most startups are not yet profitable and regularly require capital injection to remain afloat. Even those already profitable may want to raise more capital to accelerate their plans or growth.

To raise more capital, startups regularly issue new shares, which are then sold to investors who want to own part of the startup. The issuance and sale of such shares are done in a "round," and in each round, the startup negotiates with potential investors on what should be the fair valuation for the startup.

In the above chart, the startup decided to issue 20% new shares at each round up to Series B. This issuance increased to 25% and 30% for Series C and IPO, respectively. Let's break down the numbers in the chart into the following table:

| Round | Startup Valuation | Issued Shares | Founders' Shares (%) | Founders' Shares ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start Up | $0 | 0% | 100% | $0 |

| Seed | $500,000 | 20% | 80% | $400,000 |

| Angel | $2,500,000 | 20% | 64% | $1,600,000 |

| Series A | $5,000,000 | 20% | 51% | $2,560,000 |

| Series B | $25,000,000 | 20% | 41% | $10,240,000 |

| Series C | $60,000,000 | 25% | 31% | $18,432,000 |

| IPO | $100,000,000 | 30% | 22% | $21,504,000 |

Hint: to get the startup valuation, you can divide the value of founders' shares with the percentage of their shares.

As you can see, the startup's valuation increases for each round. This means that even though the percentage of founders' shares kept on decreasing (this is called "share dilution"), the dollar value of their shares (i.e., their wealth) kept on increasing.

The key to the massive jump in founders' wealth is the rapid increase in the startup's valuations. If we use Series A as the baseline, which is usually raised when the company has validated a product-market fit and seeks capital to accelerate its growth, the valuation grew by 20x between Series A and IPO.

Is this kind of valuation growth realistic? Let's check the numbers for an actual tech company that underwent a similar series of rounds toward its IPO. Airbnb is one example that has a well-publicized valuation for each series:

| Round | Date | Valuation | Issued Shares |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seed | January 2009 | $2,400,000 | 25.63% |

| Series A | November 2010 | $67,000,000 | 10.75% |

| Series B | July 2011 | $1,300,000,000 | 8.62% |

| Series C/D | August 2014 | $10,000,000,000 | 4.75% |

| Series E | June 2015 | $25,500,000,000 | 5.88% |

| Series F | July 2016 | $30,000,000,000 | 2.83% |

| IPO | December 2020 | $47,000,000,000 | 7.45% |

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_Airbnb

One caveat of picking Airbnb as our example is that we're introducing deep survivorship bias since startups that are successful to the scale of Airbnb are one in a million, but it illustrates the possibilities for rapid valuation growth in tech startups.

Between Series A and IPO, it took Airbnb 10 years to grow its valuation by 700x, or about 92% CAGR. If we use Series B as the baseline to exclude the high valuation jump in the six months between Series A and Series B, the CAGR over 9.5 years becomes 46%.

With the same benchmark of 46% CAGR, the hypothetical startup in our above example can grow its valuation by 20x between Series A and IPO within 8 years. At the same time, the hypothetical founders' wealth grew by a factor of 8.4x, or about 30% CAGR.

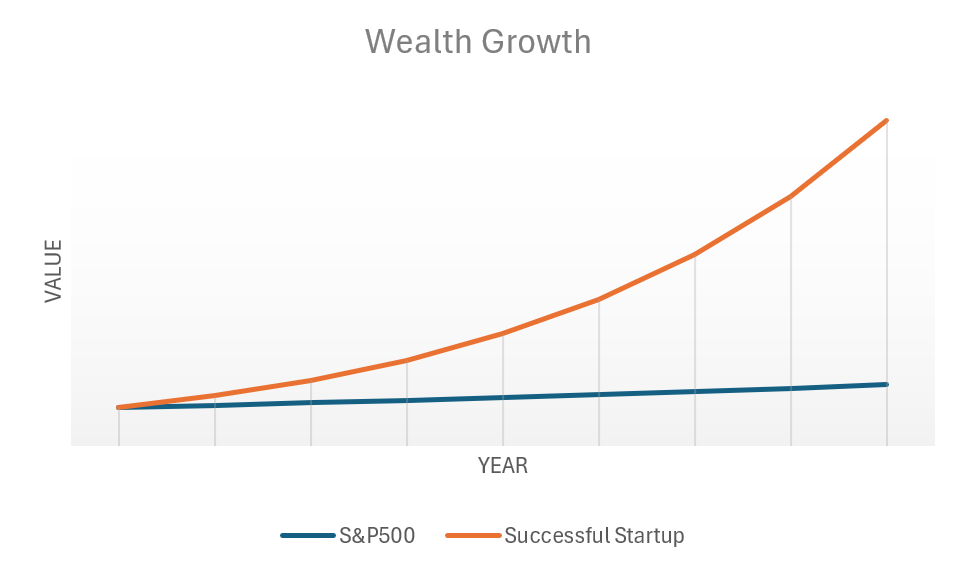

At the time of this article's writing, the 8-year return of the S&P500 index is 5.9% CAGR or about 1.58x growth for the same time period as above. Taken purely from an investment perspective, investing their time, effort, and wealth in founding a startup yields 5x more wealth growth for the founders compared to investing them in index funds.

Of course, all the above is a massive oversimplification. On one hand, the stress levels from founding, executing, and operating own startups are massively different from the passive income generated from investing in index funds. On the other hand, veteran tech founders with recurring and successful track records can accelerate the timeline significantly and produce higher value growth than 46% CAGR with their battle-tested experience.

This strong potential for growing their wealth is one of the reasons why many startup founders dare to pursue the dream of founding a startup, even though there are only 1 out of 10 odds that the next 5-10 years of their life's efforts will produce meaningful impact towards their net wealth.

So far, we have discussed the monetary gain motivations for founding a startup. One caveat from my experience is that that is usually not enough to sustain continuous efforts over many grueling years. Successful startups are often motivated by a mission they want to pursue as well, which drives them forward despite any inevitable turbulent times.

For now, let's get back to the underlying driver behind this massive wealth growth: the potential for tech startups to grow their business rapidly. Understanding why tech startups are often positioned to execute more rapid growth than their conventional counterparts is critical to understanding why many founders prefer to build tech startups instead, even though their failure risk is much higher.

Why do tech startups grow more rapidly?

Before talking about rapid value growth, let's start with the basic concept of value. All businesses generate value for their customers. I'm not talking about monetary value yet, just value, as in providing some benefit for the business's customers.

For a chain of supermarkets, for example, this value can be procuring the goods we want for our household. For a bank, the value can be access to loans and capital and an assured place to store our wealth safely.

From all the value a business delivers, they can extract portions of those values in revenues. For the supermarket example above, the revenue can be in the markup they charge when selling the goods they procured from suppliers. For the bank, it can be in transaction fees or loan interests.

As long as the value the business extracts is lower than the value the customer feels or receives, customers may tolerate the costs and continue using the business. Of course, this is a gross oversimplification. Market forces may shift the value higher or lower or even replace the business with a better alternative.

From the above oversimplification, now consider the following scenario:

Say that a tech startup builds a tech product serving a single user and generating value for them. The startup found a strong demand for their product beyond their initial user, and they want to replicate that value generation to millions of other users.

In most cases, scaling tech products is relatively easy since, by nature, it is highly automated, and we can scale up a well-engineered product in a matter of minutes by deploying more infrastructure resources to run its systems and cater to more traffic.

Compare this with a more conventional business, such as opening a supermarket. Once the business is up and running, the number of users is limited to those near that business. Sooner or later, we'll hit a limit of, at most, a few tens of thousands of regular customers.

Suppose we want to expand to the next ten thousand customers, we will need to invest in purchasing or leasing properties, spending months to renovate the said property, deploying a considerable marketing budget to advertise the new business, and waiting for months until the patronship increases to the expected regular levels, before repeating the process elsewhere.

This contrast in the friction, efforts, and time required to expand and scale up both businesses is one key reason why tech startups have higher growth potentials compared to more conventional companies, at least in theory.

In practice, the story might be slightly more complex than that. Scaling a tech product sometimes carries an overhead of scaling the ops side of the product. The intensity of the ops depends on the type and nature of the tech product.

Let's take a tech product with publicly accessible user-generated content, such as a social media platform. Such platforms often necessitate the establishment of support teams that manually review content submitted or uploaded to ensure it remains within acceptable guidelines or won't produce legal liabilities to the company.

In this case, scaling the product to millions of users would be more challenging than clicking a button to rent new servers in the cloud since the company must hire hundreds of support personnel to meet the platform's growing operational needs.

All these contrasting factors must be carefully considered when analyzing the growth potential of a tech startup. When operational overhead can be kept low, the growth potential can be many orders of magnitude higher than that of a conventional business.

Now, how does that higher growth potential translate into higher valuation?

There are many factors to consider when valuing a company in the private market (i.e., pre-IPO). One of the most consistent approaches is to value the company not just based on its current revenue level but also by considering the potential future revenue it can generate from its business growth.

Thus, startups with compelling growth stories, track records, and future plans can convince investors that their future valuation will increase exponentially compared to their present or past growths. This increase amplifies the valuation multiples for tech startups, which is a certain multiplier applied to a company's annualized revenue or sales to estimate the business's fair market value.

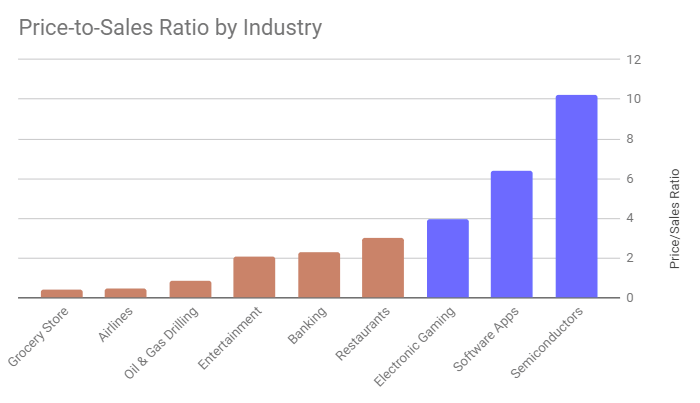

To validate our thesis above that tech companies, with their stronger growth potentials, tend to have stronger valuation multiples, we can check the price-to-sales ratio for various industries:

The general trend is that businesses on the left side of the chart have lower valuation multiples against their annual revenue, and they are generally harder to scale up. Meanwhile, tech industries on the right side of the chart have much higher valuation multiples, driven mainly by how much easier it is to scale up their future business.

Now that we have gone through the risks and reward potentials of founding a tech startup, I would be remiss if I didn't give the caution that founding tech startups is not for everyone.

Why is founding tech startups not for everyone?

A huge degree of success for a tech startup depends on the capability of the founders to execute their vision and operate the company toward successful growth. This sometimes requires an overwhelming demand for the founders to have the right mix of:

- Creative thinking to see all angles of the problem they're trying to tackle and what potential levers they can push to better align the product with the market

- Perseverance to relentlessly iterate and improve the tech product, even in the face of negative feedback or low traction

- Empathy for the customers to listen to what they need, balanced with the founders' long-term vision for the product

- Experience to avoid knowing the hard way what works and what does not (Because sometimes knowing it the hard way might be too late and kills the company)

- Conviction on their long-term vision and confidence to influence and convince others (e.g., employees and investors) to buy into that vision

We haven't even touched the part about startup capital. Founding a startup is often a capital-intensive proposition from day 0. It requires huge and lengthy R&D efforts to find and unlock value for customers and reach a product-market fit.

Some well-capitalized founders can bear the costs and bootstrap for many years, but for many others, the lack of access to capital can slow the company's growth and make it hard to compete against faster or more capitalized competitors.

This is why, as mentioned in the top article linked in this post, having access to capital from VCs can increase a startup's chance of success by 2.5 times. VCs are sometimes notorious for interfering too much in a startup's operation or vision, but to be fair, they also have the risk appetite to take a leap of faith in a startup and help fund them until the business takes off or their business model is validated (and become a sustainable business).

However, the reality is that convincing VCs that the founders' vision and execution capability are worth the risk of investing in them is like a chicken-and-egg problem.

Many VCs require proof of execution or potential traction before deciding to invest their capital. At the same time, fledging early-stage startups may not yet have the traction to show they can execute because they lack capital.

One way to get out of this chicken-and-egg causality loop is to show that the founders and/or the founding teams have proven track records in executing and operating, for example, by being a founding team in a prior startup that managed to execute growth to a certain scale. (or, even better, reach an exit, usually through IPO or acquisition)

Having a founding team with successful prior track records is one of the strongest predictors of a startup's success and usually factors into the trust that VCs are willing to give to early-stage startups, so it is worthwhile to invest some time in discussing the concept of founding teams and why assembling them is essential for startups, especially during their early days.

Why do founding teams increase the success of startups?

Since the term might not be familiar to all startup markets, let's start by defining what a founding team is.

Founding team members include, naturally, the founders of a startup. Beyond the initial set of founders, it is basically the early colleagues or advisors the founders decide to work with, execute and iterate their early vision, and rely on to give critical feedback that can make or break the product. In the words of Paul Graham:

Even if you could do all the work yourself, you need colleagues to brainstorm with, to talk you out of stupid decisions, and to cheer you up when things go wrong. --Paul Graham, The 18 Mistakes That Kill Startups

Next to finding cofounders with solid alignment on vision, values, and culture, assembling the best possible founding team (and structuring proper motivation for them through providing fair equity) is one of the most critical things that founders can do to maximize the success probability of their startup.

I'll be writing up a separate article on this topic, but in essence, there are specific qualities founders should look for in their founding team. Chiefly among them are the boldness to work in a highly ambiguous environment and the willingness to go above and beyond to solve customer needs and problems.

Why am I writing all this?

At the time of writing this article (September 2024), the tech ecosystem is a couple of years into the so-called tech winter, and conviction on the potential growth of tech startups is a fraction of what it was just several years ago.

The impact is a steep drop (some even say a reset) in tech valuation multiples, which caused many tech startups to fail in raising more funds and have to take drastic actions to ensure the continuation of their business, including implementing mass layoffs.

Yet the situation has shown a glimmer of hope every now and then. One of the strongest aggravating factors to the winter, namely the rapid increase in the US treasury interest rate that triggered trillion-dollar capital outflow from higher-risk startup funding to lower-risk treasury bonds, is starting to show signs of reversing.

At the same time, not just in my home market of Indonesia but also worldwide, there is a sense of a prevalent rut in the demand for experienced tech talents who can execute well. In some cases, this extends to aversion towards founding or working at tech startups due to the waves of layoffs that have happened on a near-constant basis these past few years.

My thesis is that we need more people who dare to start tech startups to reverse the rut and ignite a healthy demand for tech talents again. The relative abundance of experienced talents in the market also means founders will have a faster time finding and assembling strong founding teams for their startups. Lastly, with winter comes lowered opportunity costs for startup founders to take the plunge since highly paying job opportunities become more scarce anyway.

Thus, I'm sharing all the writing in this article and all the subsequent articles in this series with the hope of opening the veil a bit on the motions of founding a tech startup from scratch and how it might be an exciting proposition for more founders-to-be out there.

See you in the next one, and keep on building! Subscribe (it's free!) to get the next one delivered right into your inbox.

Comments ()